The process of writing a novel means that you read your own work many, many times, polishing the words until they shine. If you’re currently getting your own novel ‘Bridport Ready’, you’ll know exactly what I mean.

Before I got my publishing deal, I foolishly didn’t realise this would continue after I signed my contract. I knew there would be edits, of course, but I hadn’t realised quite how many layers I would add or strip away, quite how many strings I would untangle and webs I would weave. There were initial edits and rewrites both with my agent and my editor, then there were line edits that focussed in on the macro detail of the words and phrases, and after that there were more copy edits and proof edits.

A father’s treasured love for his only child

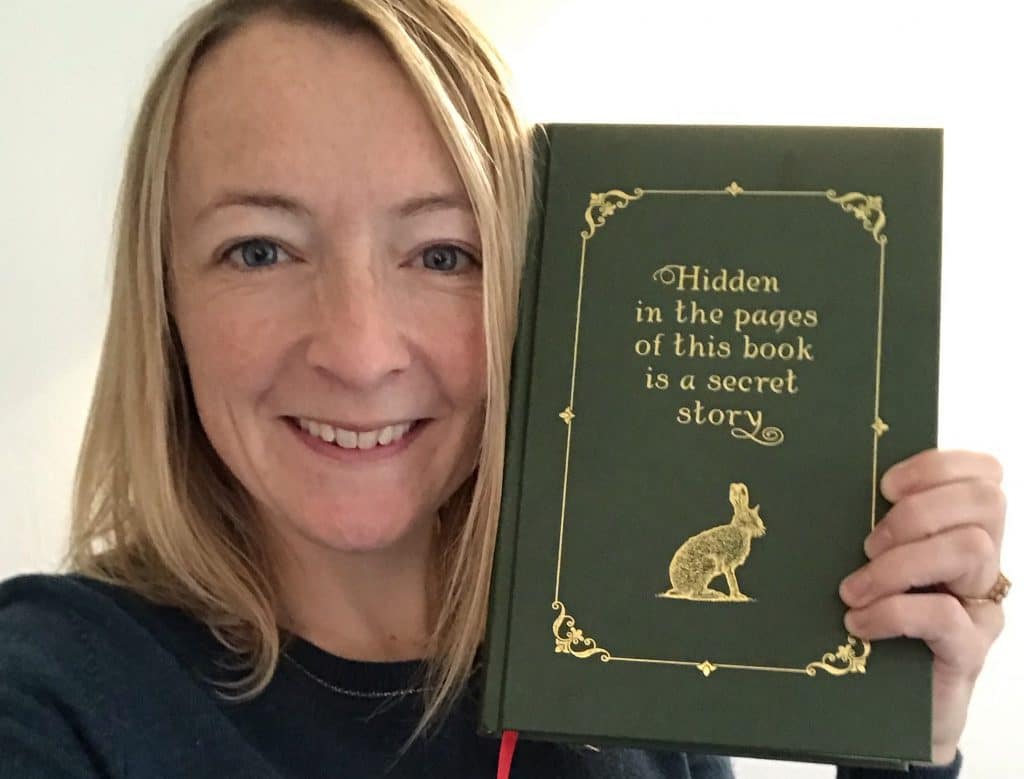

With all of these layers, it is easy to stop seeing the story, because you are so close to it. And so, when I sat down with the newly printed proof copy of my novel, The Illustrated Child, and read it as a book for the first time, what did I discover? This novel that I had slaved over for years, that I had tweaked and burnished until it gleamed, contained a hidden story within it.

Now, my novel, which came runner-up in 2018’s Peggy Chapman Andrews Award for a First Novel, is all abouthidden stories: it is about a treasure hunt, and therefore it’s packed with clues, but as I sat there reading it, for the first time I realised I had hidden things in it even from myself.

The story is about a father who creates a series of picture books starring his daughter. As the books become famous, fans uncover a treasure hunt hidden within them. But the daughter begins to suspect that the clues in the books aren’t about treasure – they won’t lead to gold or jewels, but to a secret that her dad has hidden in the books, just for her.

The first run of my novel’s proofs was a limited edition hardback in sumptuous gold and green. It had a red ribbon bookmark with a little bell attached to it, and it was made to look just like a classic children’s book, to bring to mind the story within.

My great great uncles’ influence: Heath and Charles Robinson

When I received my own copy, something about its beautiful vintage feel fizzed in my mind, and I rushed to my bookcase. There on the shelf was a copy of The Secret Garden. It was a beautiful clothbound hardback in gold and green, mirroring my own novel. This in itself is strange, but even stranger was that this particular copy of The Secret Garden was illustrated by my great, great uncle, Charles Robinson.

Have you heard of the term, ‘a bit Heath Robinson’? It means something which is ingeniously or ridiculously over-complicated, and it originates from the early twentieth century, when another great, great uncle of mine, William Heath Robinson, created humorous illustrations of contraptions, featuring bits of string and a cog or two.

Before I got married, my name was Polly Robinson. I grew up knowing I was related to the Heath Robinson brothers: we had some original drawings and many signed books, and I used to pour over these at every opportunity. My dad was proud of our heritage, and he was exceptionally pleased when I started showing an aptitude for art. ‘That’s the Heath Robinson in you,’ he would say.

Heath Robinson appears to epitomise the quirky positivity that emerges in strange situations like the one we all find ourselves in right now. In the current climate of social distancing and quarantine, Heath Robinson’s peculiar humour is oddly apt. If you search the hashtag #HeathRobinson on Instagram, you’ll find lots of his illustrations: a pen and ink sketch of a man in an armchair suspended outside his flat window by manner of pulleys and balloons; a dangling baby’s cradle, rocking in the wind, a net in place in case the child should fall. Other images on Instagram show photographs of strange inventions people have made themselves as they adapt their lives to the confines of their homes: veg patches with elaborate string patterns criss-crossing them to deter birds, a barbecue made out of a washing machine drum; a handheld drill with which to mix cocktails.

Even the Telegraph got in on the act a few weeks ago, with Bob Moran’s clever take on Heath Robinson’s cartoon, ‘The combination bath and writing desk for businessmen’, his modern version showing Boris Johnson self-isolating at home, sitting naked in a bath with writing desk attached.

It wasn’t until I was a bit older that I realised Heath Robinson was one of six siblings, three of whom were artists. Though W Heath Robinson was the most famous, his brothers Charles and Thomas were also exceptionally talented, and it was Charles’ book that bore such a strong resemblance to my own.

Generational ripples

My publisher had no idea of the connection: it was just one of those magical things that has happened as part of this writing process, and it felt to me as if my distant relative had extended his hand through the generations and reached out to me.

When I began writing The Illustrated Child, I had no idea how much of an influence the Robinson brothers would have on my work, and as I sat reading the proof copy of my own novel, I saw things I hadn’t noticed when I was writing it: echoes of the Robinson brothers’ influence run through the book like an underwater stream. There are strange inventions and contraptions in my story, drawn from my obsession with Heath Robinson’s comic work, and because my novel is about children’s books, it is packed full of descriptions of pictures and paintings, the influence of my great, great uncles’ stunning illustrations shining through.

I have been a full-time author for a year now. I’m currently deep in the edits of my second novel, and working on the premise for a third. One day, I would like to write a book about the brothers who set me on this path: their lives, their own influences, and the legacy they have left behind them, like a treasure trail of clues, just for me.

Polly Crosby’s debut novel, The Illustrated Child is out on July 9th.

Pre-order it here